Reading time: 7 minutes

Before we dive in, I’m hosting a free 30-minute Lightning Lesson on Maven to celebrate the launch of a new cohort-based version of Sell the Idea. If you’ve ever struggled to get someone to understand or see the value in the work you’re presenting, this free lesson could help.

Join the 400 designers and creatives who have already signed up.

A heavyweight boxer has won 11 of the 12 championship rounds on points.

The judges ringside know it. The audience knows it. The outclassed, outgunned opponent knows it.

And yet, in the final three minutes of the 12th round, just one moment of carelessness giving in to heavy hands, one moment of distraction or hubris, all of which expose the chin, and the champ-to-be can be caught by a haymaker and find himself out cold on the canvas. All the industry and poise of the previous rounds have turned from ‘contender’ into ‘cautionary tale’.

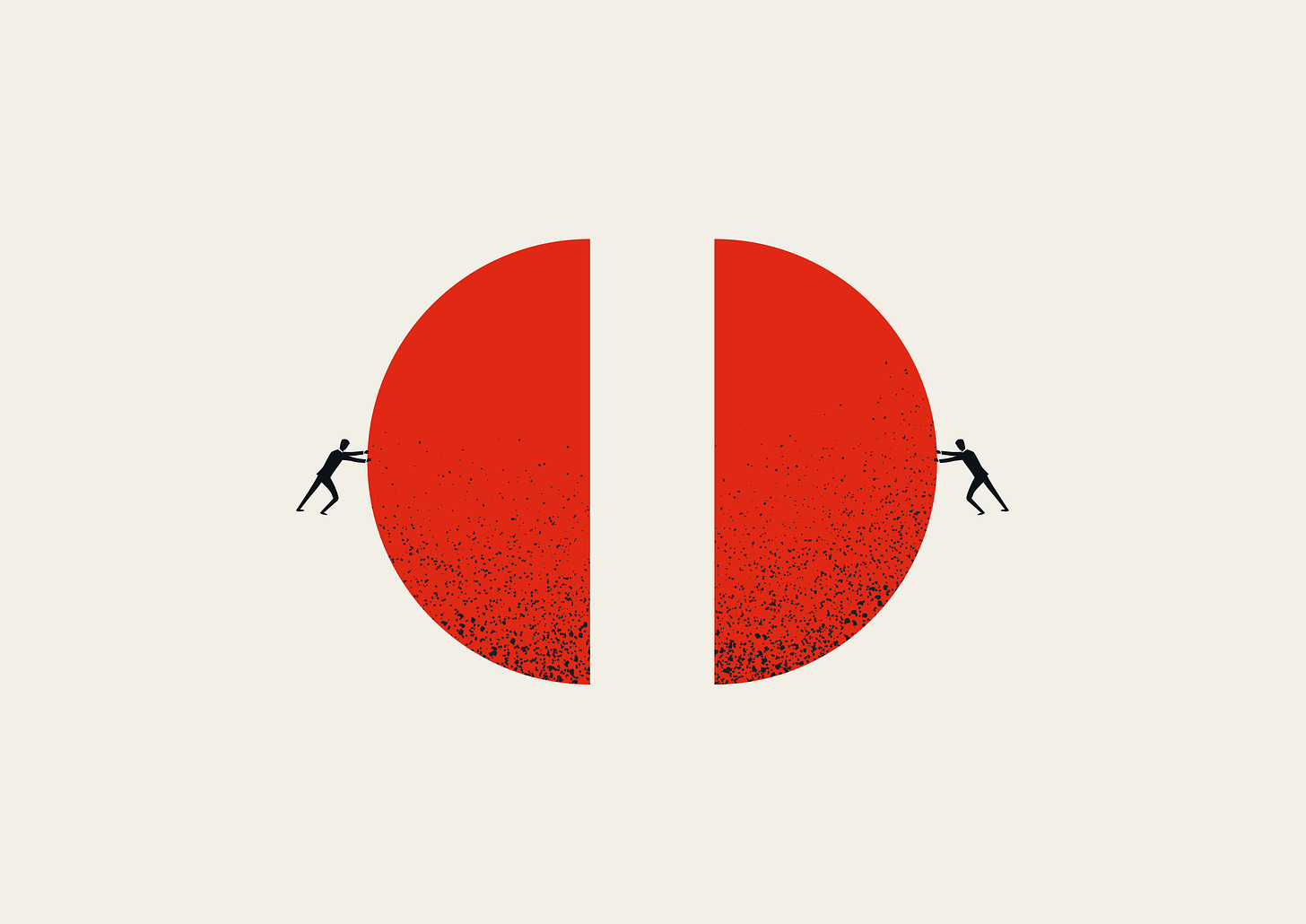

Like the opponent losing on the scorecard, mediocrity always has a puncher’s chance. And at no point other than the final three minutes, when it has nothing left to lose, does it really get in your face and start to swing.

In every creative project, we are never more than one 12th-round decision away from taking something exemplary and turning it ordinary. Or worse.

Early-stage vs. late-stage decisions

Decisions in the 12th round are not the same as those made in the first, second or third. As the work evolves from concept to completion, the context in which decisions are made shifts dramatically.

We know the following:

Early-stage decisions have a foundational impact and set the tone for everything to come. Late-stage decisions, on the other hand, are often about refinement and optimising what has already been established.

At the onset, decisions bear flexibility, and missteps can usually be corrected without significant repercussions. Towards the end of a project, there is tension with time; the pressing need to meet an impending deadline will force teams to make decisions for the first time via triage. What can be simplified, what can be postponed, and what can be dismissed altogether?

And, of course, early-stage decisions have deferred expectations and therefore reduced pressure, leading them to be more thoughtful and well-rounded where the ideal of creative merit is the aim. In the latter stages, stakeholder influence will be more pronounced as production moves to delivery and ROI.

These distinctions are obvious in reflection but manifestly indiscernible while we are in the ring. It’s also a limited vocabulary. We have surrogates for what we really need. Idolaters of agile and the associated project management frameworks won’t enjoy this, but one could argue they are partly to blame. While they can excel at managing tasks and timelines, they fall short of subtle and profound changes in decision-making from the beginning to the end of the creative act.

So, what’s the outcome?

We can underestimate the impact of late-stage decisions, and when we do make them, they are often made hastily.

Have you ever experienced 100 minutes of rampant thrill and joy in a feature film, only to feel betrayed in the final 10? Maybe you’ve welcomed a beautiful, useful digital product into your life that’s made intolerable by an intrusive ad model. How about bad lighting in an architectural work of art? A jarring soundtrack. An over-edited photo. Too much salt. Or, I’ll say it…that time the logo was made too goddamned big.

Let’s forget what decisions should or shouldn’t look like at each stage.

Instead, we can consider three afflictions that cause teams and individuals to lower their guard in the 12th round.

An exposed chin

To be clear, these three afflictions will be suffered by the most capable teams first. If, however, we maintain an alertness to them, we can prevent the last-minute KO.

Affliction one is momentum.

After initial promising traction, there can be a belief that a project’s momentum will carry it through to a successful conclusion. Overconfidence in early success (read: hubris) inflates the sense of security of a project, and we underestimate the impact of decisions after the bulk of work has been done.

Likewise, if an approach has carried a team to where the end is in sight, they will probably favour the ‘tried and true’. Why innovate now when 11 rounds are already banked? Proximity to completion creates a sense that the essential tasks are done and there is an inevitability of success.

The second affliction is fatigue.

Tired, heavy hands will meet you at some point in your project. By the very nature of a creative endeavour nearing its end, resources will be depleted. Time, budget, and energy. This leads to a focus on conservation and efficiency rather than optimal decision-making. It also dramatically changes appetite to request additional investment that might be needed, based on the fallacy that past investments (and the energy that went into them) must be preserved at all costs.

Fatigue also makes us less likely to take feedback. It creates a reluctance to revisit earlier decisions and repeat spent effort. It can also lead us to make unchecked decisions that really do need an outside opinion. These small deviations from previously set standards get normalised and can quickly accumulate.

The third and final affliction is distraction.

As teams are deeply focused on finalising a project, there can be a failure to notice the need for a shift in strategy. External forces are not in stasis while the project meets its completion. The market, consumer preferences or competitor actions all change.

Lastly, distraction can create an illusion of unanimity. Dissenting opinions might be voiced less towards the end of a project, leading to decisions that everyone appears to agree on but which might not be the most creative or effective. If a boxer refuses to see the possibility of his opponent’s change in tactics in the final round, teams can just as easily fail to introduce new ideas or challenge the status quo.

The sweet science

We’re here now — I’m going to stretch this boxing analogy as far as possible.

What does a career of succumbing to mediocrity in the 12th round look like? There is peril attached to it, as there would be for the boxer. You can end up punch-drunk.

The repeated blows will leave a creative team or individual disorientated. It can lead to a loss of direction, being unable to effectively plan the next move, or a dulled sense of innovation due to repeated setbacks. Standards can also slip. The once-tight guard gets looser, and mediocrity can become the norm. Or the result will be diminished reflexes where originally sharp instincts for meeting a market opportunity become sluggish. Perhaps worst of all, against better counsel, the creative will start to get in the ring for the wrong reasons.

All that said, we should cut ourselves and others some slack.

No one sets out to make something of poor quality. In the same way, the boxer doesn’t get in the ring to lose. It’s just that mediocrity is a real S.O.B. of an opponent. But it’s a good reminder…

The fight isn’t done until it’s done.

Keeping creativity alive is keeping the hands up — against all hubris, tiredness or distraction — through to the closing bell.

Like this issue? Consider sharing it with your colleagues internally or on social media. Alternatively, refer a friend to be eligible for rewards. Thank you for subscribing.

If you’re looking for other ways to keep creativity alive as an individual or team, my course Sell the Idea can help you pitch and present your ideas effectively. Readers get an exclusive 20% off the new cohort-based course on Maven. Most companies reimburse Maven courses — check with your manager or L&D team.